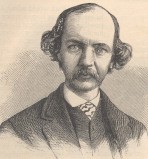

Sketch of Frederick Law Olmsted in 1869 while he was working on Central Park in New York City. (Copyright expired.)

Acclaimed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted created amazing gardens in Central Park for the City of New York as well as the gardens of Biltmore House in North Carolina after the Civil War. In the early 1850s Frederick and his younger brother John Hull Olmsted set out for Texas. The elder brother came to observe the land and its people, and to judge the impact of slavery in the new state. John suffered poor health; hence his doctor advised the trip to Texas.

The Olmsted brothers traveled to and from the Sabine River between December 1853 and May 1854. They rode horseback from Gaines Ferry on the Sabine to Austin, then to the Gulf coast at Indianola, westward to San Antonio and the Hill County and down toward the Rio Grande before returning to Gaines Ferry by way of Galveston and Houston.

As the pair crossed the Sabine River they discovered a partially populated region, with log cabins and slave quarters, very little strenuous labor on the part of landowners, and cattle freely roaming tall-grass prairies. Connecticut-born Olmsted was not impressed at all, to say the least. Throughout the region most meals, whatever time of day, consisted of fresh or salt pork, cold cornbread, boiled sweet potatoes accompanied by a revolting beverage Texans called coffee. Cornbread was made of meal, water and salt, stirred and then poured into a kettle covered with coals.

When they arrived in Austin with high expectation, the brothers found a nasty hotel ranked best in town, burnt fresh swine and bulls, decaying vegetables, and rancid, starchy, mealy, jellylike substance called butter. Frederick began a mission to find decent butter somewhere in Texas with all the cattle on prairies.

The next stop was the Texas Hill Country recently settled by German emigrants. For the first time they enjoyed Molasses Cakes and Candies. Yet in that village there was no butter, wheat bread or fresh meat. They were able to purchase salt meat, crackers and poor quality raisins.

In Neu Bransfels (sic) dressed meat and beef sausages hung from butcher shop windows. A dinner one night included a choice of two meats; neither was pork or fried; two dishes of vegetables, salad, compote of peaches, coffee with milk, loaf of wheatbread and sweet butter. The two brothers thought they were in heaven. Plus, the house, kitchen, and table were spotlessly clean. They enjoyed buttermilk, eggs, pfannekuche (a German delicacy similar to pancake-omelet mixture) eaten with sugar and butter. Another meal consisted of a fat turkey.

Fifty miles to the south was the village of Castroville where the pair found fifty acres of corn growing to feed livestock and humans as well as to sell to the Federal troops nearby. Kitchen gardens consisted of wheat, peas, potatoes, blackberries, and mulberries. One meal served them was venison, wheat bread, eggs, milk, butter, cheese and a crisp salad, even in the chilly springtime. Here they discovered locally ground flour that in eastern parts of the state was imported from Ohio. Needless to say, the Olmsted brothers realized there was delicious food available in parts of Texas.

As they neared Galveston the men encountered bananas, oranges, and lemons. These were covered in cold weather, but somewhat bountiful in local markets.

Frederick Olmsted had a talent for observing and recording this new world on both the large scale and the minutiae. His writings include definitive descriptions and acute criticism. He was not a man to mince words. Frederick Law Olmsted was a known abolitionist. His views were that persons owning slaves were lazy and filthy folks who never taught the slaves to cook or clean or even tend livestock. Others from New England and the Midwest shared his broad bias of eastern Texas. Yet, he praised the German emigrants profusely. Needless to say, Olmsted did not leave Texas with any remorse.