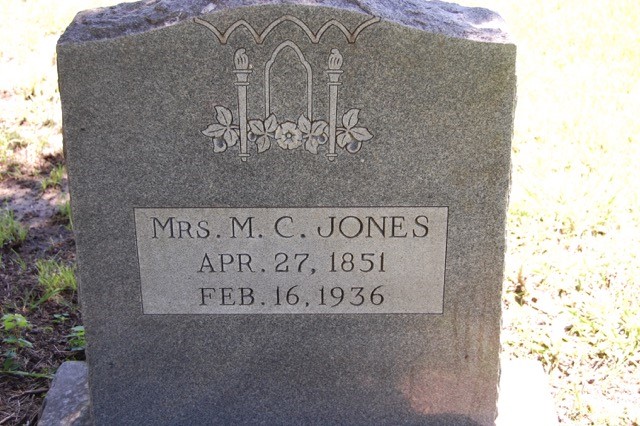

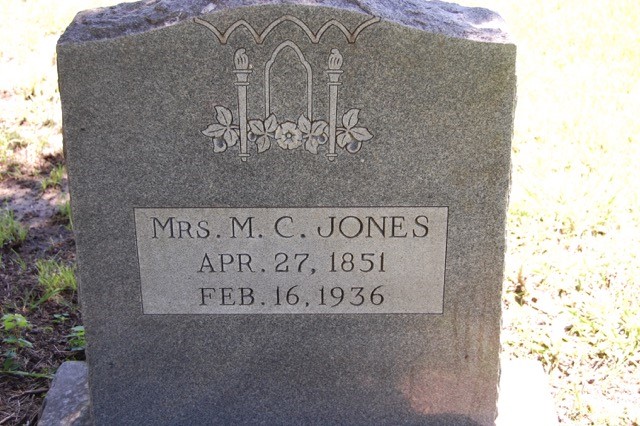

This is the gravestone for Mrs. Missouri Caroline Wall Horton Wallace Jones in East Mount Cemetery at Greenville, Texas. She was an independent woman who managed her property. What her first husband, Austin Horton left her at his death in 1873, she still held after two more husbands and eight children when she died. A remarkable women ahead of her time.

For more than two centuries, women in America were considered too delicate to handle finances or the burdens of business ownership under a variation of British Common Law. Close male relatives controlled property rights for women.

Louisiana, Mexico, and other governments that were part of the Spanish Colonial System used what is known as Civil or Justinian Law. Women there were thought capable of controlling their own property rights. One woman here in North Texas made good use of that law.

Eleanor Langford led an unusual life. Born in Kentucky, she met and married Maxwell Langford in Clarke County, Arkansas in 1822. By 1825, Maxwell was dead leaving Eleanor with two young children. That same year Maxwell’s parents Eli and Mary Langford decided to make their fortunes in Austin’s Colony of the new country of Mexico.

Eleanor and her children came to Texas with her in-laws where Anglo settlers were given up to a league of land (4,428 acres) for grazing and a labor (177acres) for cultivation. They must become Mexican citizens and adopt the Catholic faith. Eleanor and her children occupied a small cabin on the Langford’s property. Because Eleanor was a widow with children she was allotted the maximum amount of land but did not apply in Austin’s Colony.

Shortly after the extended family was settled on Attoyac Bayou, Eli began to make frequent calls on Eleanor. Sometime between 1828 and 1830 Eli moved in with Eleanor. By 1832 the two along with her children relocated north to Red River County.

Eli and wife Mary never divorced and Eli never married Eleanor, although they would have four children together. In September 1834 Mary applied for a league and labor under Mexican law. Her grant was approved on November 8, 1835 as the Texas Revolution began. Mary and her children joined the Runaway Scrape crossing the Sabine River as word arrived of the fall of the Alamo in March 1836.

While many settlers returned to the Republic of Texas Mary remained in Sabine Parish with three young children until 1854. She abandoned her claim for land but it was already approved and filed with the Texas General Land Office.

For tax purposes both Eli and Eleanor claimed head of household. Between 1833 and 1835 both were arrested and charged with adultery; neither was found guilty. Eleanor claimed her league and labor and eventually owned 2,000 acres in Red River County. The remaining claim she later deeded to her children. Because Mary’s claim was confirmed, even though she forfeited it, Eli could not claim land in Red River County. The couple lived somewhat peacefully for years there.

When Eleanor’s children were grown they settled in Hunt County. Eli and Eleanor moved to Tyler where Eli returned to the bridge building business he operated earlier in life. He simply disappeared in 1850. Eleanor decided to move to Greenville to be near her children. There she became a charter member of the First Baptist Church. The 1860 census showed she owned seven slaves and her daughter Rosetta was owner of eight slaves. Eleanor died in 1861 and was probably buried at East Mount Cemetery. Some of her descendants still live in the area. Eleanor’s choices allowed her to accumulate a vast amount of land and money. As a widow she had complete control of her own real property.

The second widow we meet was Missouri Caroline Wall, born on April 4, 1853 and resided in Greenville for the rest of her life. Missouri Caroline or M. C. as she preferred, married Austin V. Horton on April 21, 1870 at the age of seventeen. Austin was the son of James R. and Mary Merrill Horton, early settlers in the county. He served in the final years of the Civil War on the Confederate side. Between 1867 and 1872, Austin purchased 207.25 acres of rangeland and a town lot. Some of the grazing land was even purchased on the courthouse steps at delinquent tax sales. In addition to his real property, Austin owned three horses, three oxen, one wagon, about 25 head of cattle on the open range and 20 head of hogs. He and Missouri Caroline owned a house, farm tools, and furniture.

In 1872 Austin and Missouri Caroline became parents of a healthy young boy. While in Collin County on business in 1873, Austin died, leaving a young wife and small child. However, the will he made named Missouri Caroline executrix of his estate. Missouri Caroline’s father Henry F. Wall provided the surety and good solid advice for a long time. She had full control of the estate. Now let’s see how at age twenty Missouri Caroline fared as a female landowner.

In the 19th century, especially on the frontier, few widows remained unmarried. On November 17, 1875 Missouri Caroline married M. W. Wallace from South Carolina. Very little is known about Wallace other than he was fourteen years older than his wife, had served in Wade Hampton’s Legion during the Civil War, and somehow arrived in Greenville. He paid no taxes before the couple married so was he new to the county when they met or was he a tenant? The couple had three children, Wade Hampton, Borgia, and George Washington Wallace. M. W. is believed to have died around 1882 but cause of death or burial site are unknown. Missouri Caroline did obtain guardianship of all four children at that time.

One year later the widow with four young children married C. L. Jones. Again, little is known about Jones. The couple lived on her farm as she and M. W. Wallace had. Missouri Caroline and C. L. Jones became parents of four children; Walter S., Joe M., Vivian, and Mabel. Through a timespan of almost twenty years, Missouri Caroline bore eight children, all of whom reached adulthood.

When C. L. Jones died in 1899, Missouri Caroline never married again. She continued to live on the farm near Ardis Heights that she inherited from her first husband, Austin V. Horton. When Missouri Caroline died at the home of her daughter Mabel in Sulphur Springs in 1836, she left her property to be divided between all her living children. Neither of the two later husbands owned the land; however they lived there with her. Considering the financial struggles in Texas from 1873 to 1936, Missouri Caroline Wall Horton Wallace Jones managed her land and finances well.

Our last widow did not fare so well. Her story is typical of 19th century widows. Rachel Arnold was the wife of Lee Arnold, Sheriff and Alderman of early Greenville. While living within the city limits, Lee Arnold acquired farm tools, work oxen, 50 milch cows and 20 head of hogs. At his death Arnold’s probate showed a house and household goods valued at $2,000. He named James Bradley, an esteemed attorney as administrator. In January 1855 Bradley accepted the position and did nothing, absolutely nothing for Rachel or her children.

Rachel and the children had no income, no food, no clothing; basically they were destitute. She could not legally manage the estate her late husband left. During the December term of court in 1856, Lee’s brother petitioned for guardianship of the five minor children and Lee’s widow. The guardian finally sold the house in February 1859 for $800. No cemetery records or marriage records or census records exist after Lee’s death for Rachel. She became an invisible woman in history.

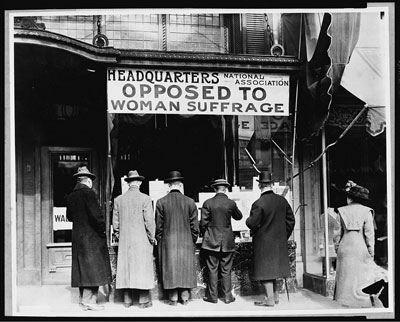

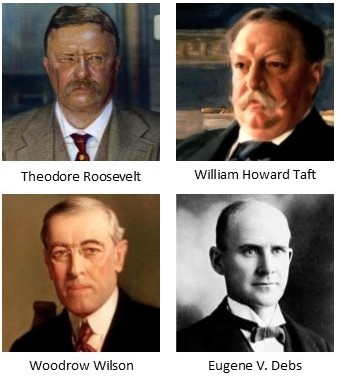

Realizing I knew more about conditions in Europe than in America in the early years of the 20th century I decided to examine the politics and political movements Americans were facing. The best place to find these critical issues was to look at the election of 1912.

Realizing I knew more about conditions in Europe than in America in the early years of the 20th century I decided to examine the politics and political movements Americans were facing. The best place to find these critical issues was to look at the election of 1912.