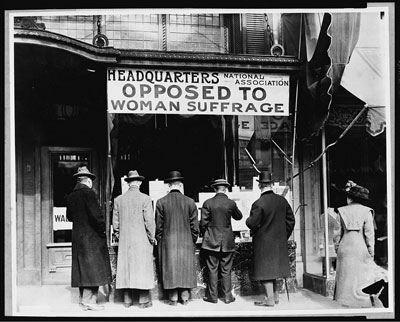

Notice that only men are looking at the materials displayed in the Headquarters of the Nation Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage while the woman doesn’t seem too interested.

For a brief time women in Texas were excited, hopeful, and possibly in disbelief in the summer of 1918. For the first time ever women in Texas could vote in local and state elections! It had been a long fight, and unfortunately lasted only that summer. But on July 26, 1918 over 386,000 women marched to polling places, cast their votes, and felt like a real human being with equal rights.

Women were considered helpless and fragile since early settlement in the United States. Any man with considerable money believed it was his marital duty to care for delicate wives, relieve them of the burdens of owning property and controlling any or all-family business themselves. Of course, we know that was an excuse for controlling any inheritance or money the wife had. Voting was a threat to many men. Voting could change the status quo for better schools, playgrounds, parks, public health, sanitation, working conditions, and improvement in life generally at the cost of higher taxes.

The fight in Texas began with the Reconstruction Constitution in 1867. A proposal that all persons over the age of 21 could vote never made it out of committee. Prohibition and women’s suffrage seemed to really set off the men who controlled life in Texas.

In 1893 the Texas Equal Rights Association began a campaign for women to vote. This lasted until 1896, but did attract local and state newspapers. For the next twenty years various Women’s Suffrage groups would pop up and then as quickly evaporate. The Association Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage was organized in 1915 to oppose women voting. World War I would stop that, though.

During the war, women organized and managed Red Cross drives. They started libraries on military training centers, opposed red light districts and sale of alcohol to young soldiers, and frequently took over the family business while the husband served in the military. All of this helped to soften opposition to enfranchisement.

In 1915 the issue became a hot topic; a vote in the House had less than a 2/3 majority required for a constitutional amendment. However, Governor William P. Hobby who replaced Governor James E. Ferguson when he resigned claimed that primary votes did not require a constitutional amendment. A simple legislative act passed in a called session. More than 386,000 women in Texas registered to vote in 17 days. Hobby who was running for governor carried the primary on July 26, 1918 thanks to grateful women.

In August 1918, some 233 Democratic County conventions went on record in favor of women’s suffrage. The following month the State Democratic convention endorsed it. Hobby recommended to the Texas Legislature in January 1919 to amended the Texas constitution to include women voters and that persons of foreign birth be allowed to vote only after acquiring full citizenships. There were no dissenting votes, but resident of Texas still must approve the amendment.

Women voters held a vigorous campaign led by Jane Y. McCallum of Austin but the amendment proposal lost by 25,000 voters state wide. The same year the United States Congress proposed the 19th Amendment allowing women the right to vote nationwide. It was opposed in the South where men thought it would threaten states rights and control of elections. They feared that Black women voters would increase the political influence of Black men.

Texas, however, voted to ratify the 19th amendment, the first of only three former Confederate states to do so. So, next Thursday, July 26, give a shout for women’s right to vote if only briefly.