Driving down a country road, you see an old cemetery and wonder who those people were and how long ago did they live there. Historic cemeteries, and they are all historic, are some of the most valuable resources in Texas. From the meagre information they provide, we have a directory of the early residents and settlements. They reflect ethnic diversity and the unique populations of an area.

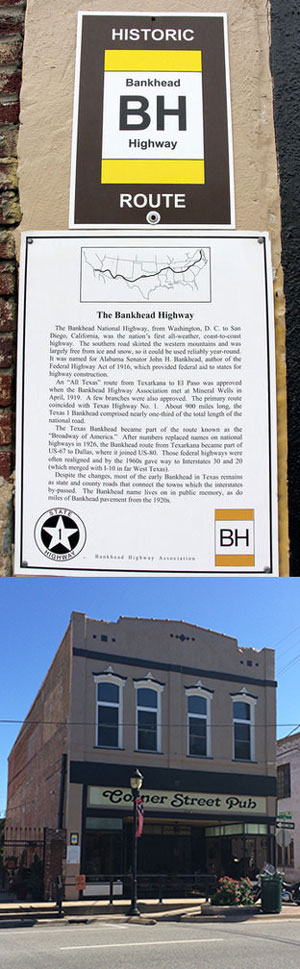

Unfortunately, many of these irreplaceable resources are at risk and have been for years. To counter that, the Texas Historical Commission (THC) has two ways to commemorate these old burial grounds. The first is the Cemetery Preservation Program. Members of the Hunt County Historical Commission, led by John Byrd of Quinlan, have located more than 100 cemeteries in our county. Many are in very good condition while others need a little or a lot more tender, loving care. Those are listed as Designated Historical Cemeteries.

Presently the THC is working to determine the conditions of these cemeteries. Many of the cemeteries have inventories and mark plats of the grounds. That is wonderful. Our clay soil is not favorable to old, or even new, gravesites. To learn more about this project and more about cemetery laws go to http://www.thc.texas.gov/preserve/projects-and-programs/cemetery-preservation. Then if you are interested you can contact me to join the Hunt County Historical Commission.

We have encountered some disturbing news about cemetery preservation here in Hunt County, but overall, we are much luckier than neighboring counties. Before the end of World War II, fortunes were made on Hunt County land in the form of cotton farms. As the economy worsened, more and more lands were obtained to plant more cotton. Cotton growers planted the prized seeds right up to a house. Land owners began to prohibit tenants from raising cows and hogs, or even a small garden patch.

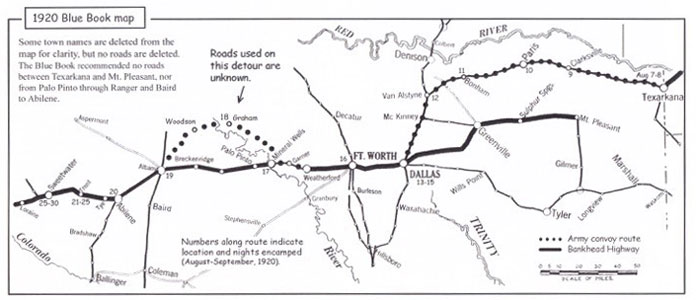

If you walk vacant lands throughout Hunt County, you will locate small cemeteries on the banks of our many creeks. Higher lands were reserved for farming cotton. Every inch of fertile soil was used.

Over the years I have heard some tragic stories about rural cemeteries throughout the State of Texas. Almost every county had at least one Poor Farm where indigent men and women, and occasionally children lived. They worked the county farm to grow food for themselves and prisoners in local jails. Sometimes prisoners who were trusted were sent to the Poor Farm to help with crops, but with a guard closely watching on horseback.

When someone died on the Poor Farm and had no family, they were buried in the small cemetery there. After Poor Farms were sold in the late 1940s, new owners frequently removed all the simple markers, hauled them to a ditch beside the road and continued to farm more land.

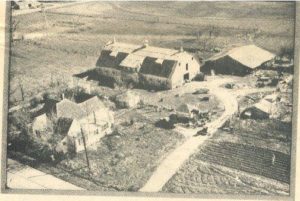

We have heard rumors of such events here in Hunt County but have never located one. We recently learned of an abandoned cemetery near the Fannin/Hunt/ Delta County line. In a ditch by the roadside are several pieces of tombstones, store bought, not homemade. We think we have a photograph of the cemetery about 1910 with two obelisks, but was it exactly where the remaining stones are scattered today?

These are known as unknown cemeteries and/or abandoned cemeteries, the second program of THC. We try to identify the real location, to determine if it was a family cemetery. It is a challenge. Come join us.