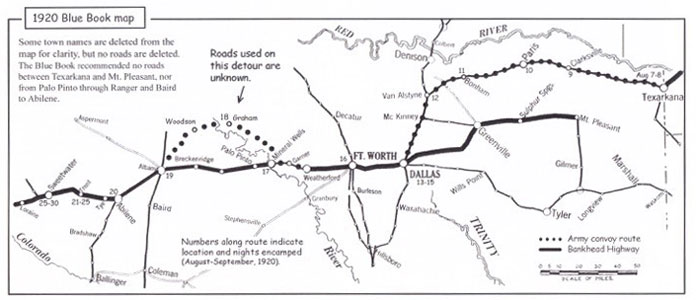

Map of the Bankhead Highway route through northeast Texas. From Texas Highway No. 1, The Bankhead Highway in Texas: A Highway History and Guide to the Earliest Texas Route. An excellent work by Dan L. Smith (2013).

In 1903 Henry Ford began mass production of automobiles, an event that drastically

altered life around the world. But not surprisingly, the automobile had few, if any, good roads to travel. Travel and transportation of goods were still challenges. Over the next fifteen years, counties and states began to upgrade their roads. In some cities, roads were paved, but costly roadwork was not the norm in rural areas where roads were usually dirt and gravel. That meant problems galore in rainy weather.

With the availability of more motor vehicles, numerous Good Road Associations sprang up almost overnight. Each promoted good roads in their regions, pointing out that improved roads would reduce travel costs, bring greater reliability and lower freight rates. Since this was barely fifty years after the Civil War, many of this proposed roads carried the names of Civil War heroes, much like those Confederate monuments erected at the same time.

The associations were public relation groups, not road builders. The major roadblock (no pun intended) was lack of funds. Only the federal government had that kind of money; but many citizens questioned the Constitutional right to build roads. Finally, the Supreme Court approved and Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. Sometimes called the Bankhead Bill in honor of Senator John H. Bankhead of Alabama who pushed the bill through, it was signed into law soon after by President Woodrow Wilson, an automobile devotee. Federal funds were available and roads needed building. But each state must have an established highway department, of which Texas and South Carolina had none. That little minor detail was soon rectified in both states.

The route of the roads needed to be laid out. A group of men known as “pathfinders” scouted existing roads that met the following criteria: 1) shortest distance; 2) condition of current roads; and 3) the amount of local support to aid with cost and future maintenance.

This marker recognizing the route of the Bankhead Highway through Greenville is located on the building now housing the Corner Street Pub on Lee Street.

Bankhead Highway entered Texas at Texarkana and exited in El Paso, being the longest portion of the highway that began at the White House in Washington, D. C., and ended in San Diego, California. Here in Texas it was also known as Texas Highway 1. It came south through Greenville on Stonewall Street, turned west on Lee Street, south on Wellington to O’Neal where it connected with what is now Texas Highway 66.

Within weeks of President Wilson signing the Bankhead Bill, the United States was in World War I. The horrible road conditions that slowed armies to a crawl awoke the military of the need for military highways in the U. S.

The Bankhead Highway would be chosen; after all it was an all season transcontinental highway.

On May 7, 1920 the U. S. Army’s Second Transcontinental Motor Company left the White House on its way to San Diego. Estimated time was 84 days. In the processional were 30 trucks, 10 Dodge automobiles, and 160 men with 32 officers. It was to be a National Road for National Defense; an opportunity for field training, to test equipment, and to recruit men for the Army motor corps.

That summer happened to be the rainiest on record. Travel through Mississippi and Arkansas was a disaster. When they arrived in Texarkana, the commander decided to not take the official route through Mt. Pleasant, Sulphur Springs, Greenville and Rockwall to Dallas as the route was in low lying areas part of the way. Instead, the route went through Clarksville, Paris, Honey Grove, and Bonham before reaching Dallas. That route is on a high ridge but the poor towns, including Greenville, were left out after long hours of preparations to welcome the procession.

Yet, the route through Greenville became part of the official Bankhead Highway or Texas Highway 1 during the heydays of the 1920s. In 1926, the Texas Highway Commission decided there were too many names to remember; numbers were easier to use on highways. The arrival of Interstate 30 after World War II cut traffic on the Bankhead. But it served its place in the early years of the Automobile Age.