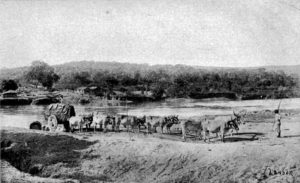

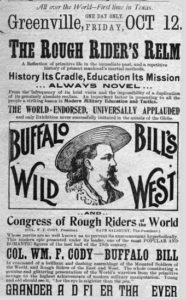

It was a grand day when Buffalo Bill, Congress of Rough Riders, and Annie Oakley visited Greenville. (Photo from author’s collection)

W. Walworth Harrison and his mother Mrs. Will N. Harrison probably were the first historians in Hunt County. Mr. Harrison loved newspapers, especially the three local papers, and frequently made notes on pages or copied the highlights and filed them away. When I worked at the Genealogy and Local History Department at the library named in his honor I copied many of his notes. Hence the sources of today’s article.

Three big events occurred in Greenville in 1900 are noteworthy. That summer a Greenville Street Carnival was held in July. Parades, balls, more parades, exhibits, and a Firemen’s Racing contest kept the crowds entertained for two days. Even though there were printed programs, organizers often adjusted the events to suit visitors.

In late September handbills began to appear all over town. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was coming to town for one day in October. This time the Congress of Rough Riders was in the festivities along with cowboys, Arabs, Mexicans, German and English soldiers, Cossacks, Gauchos, and other riders. Miss Annie Oakley would display here talent with a carbine.

Finally, the very first football game took place in McKinney when the Greenville team took the train over there to clash with their team. This was so new that neither team had a name or mascot. In fact, records for Greenville High School show no coach employed by the school. Who won? Who knows because Mr. Harrison neglected to make a note of that important question?

But now let’s look at the year 1900. Was it the beginning of a new decade and new century or the last year of the current decade and century? If you remember the debate in 2000, you have an idea of the conundrum.

It’s similar to arguing that 0 is the first digit in our numerical system or is it at the end when joined with a one to form 10, or both? Is the ace in a suit of cards the highest or lowest? This discussion was argued throughout the world from 1899 until January 1, 1901. In most places a convenient solution was arranged. Why not celebrate on December 31, 1899 and again on December 31, 1900?

Around the world no one seemed to mind having two festive events. No one complained of having celebrated a year earlier. It was a huge celebration of New Year and New Century twice.

From his notes and comments, I get the idea that Mr. Harrison was not a big party guy. As a result, I found no descriptions of parties at the homes of the very elite in town, of which the Harrisons belonged. I found no Watch Night parties at churches, although 1900 may have been too early. I found no lively excitement in the local saloons and no long list of those put in jail.

Back in 2000, I read local newspapers for news of 1900 festivities. I found that dinner parties made the newspapers but were not necessarily the largest gatherings in town. I do remember reading that those nights, boys and young men shot off fireworks. However, I recall wondering how the working class celebrated. I thought since wages were not lavish, most enjoyed a quiet gathering if they celebrated at all. So what and when did you celebrate the New Year, the New Century and the New Millennial of the twenty-first Century?