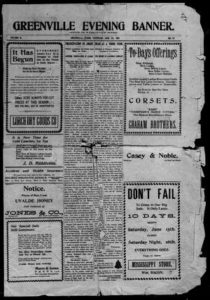

Well-fed guests partaking of a fine meal at a 19th century dinner party. Maybe a little too fancy for ante-bellum Greenville. (NPR)

This year I decided it was time for a little pizazz in my dining room. How exciting can a room be if the walls are painted “file folder yellow?” While the paperhangers were busy prepping walls and hanging the paper, I began to think about dinner parties I could give.

I found myself thinking about early settlers here in Greenville and Hunt County I would have enjoyed dining with. The list included one couple, three men and two very interesting women. You may be surprised at my choices. You may not have heard of some or even all of them. So sit back and enjoy my Fantasy Dinner.

The first person I would invite was Lindley Johnson, probably the very first settler in the Greenville vicinity. He arrived in this part of Texas in 1833, volunteered in Texas Rangers and received a commission as Lt. Colonel before he acquired a considerable amount of land through grants. In the 1840s Johnson and his family settled on land where KGVL/KIKT radio station is located. He appears to have been the first moneylender in the area. His probate in 1858 showed considerable loans and a fairly lengthy bar bill. Definitely Lindley Johnson would be invited.

I would also invite two attorneys, neither for their legal prowess, but their collection of early Greenville history. Alfred Thomas Howell was raised in Virginia, trained as a lawyer at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. After graduation, he headed straight to Texas to make his fortune. After trying to build a clientele in Red River County and Lamar County with little success, he came to Hunt County, where the court was full of fraudulent land claims. Along the way he wrote colorful, honest letters to his brother back in Virginia. The brother and his family saved the letters until donating them to the Tennessee State Archives. They are priceless.

Linton L. Bowman loved serving as the Eighth District Judge when that was a circuit court. Every time he called a recess in a trial, he visited with the audience (people came to watch court in session like we watch television or movies). His collection of notes regarding the Northeast Texas area from the Civil War until about 1920 is exceptional and wonderfully curated at Texas A&M University Commerce Archives.

Eleanor Carruthers Langford was probably the most interesting and fearless woman ever in Hunt County. She was born in Kentucky but moved with her family to Arkansas Territory where she married Maxfield Langford in 1822. Her husband died before 1825 leaving her a widow with two small children. When her in-laws decided to move to Texas in 1825 she followed and made her home in a small cottage on their property. Sometime between 1828 and 1830 her father-in-law Eli Langford moved in with Eleanor, abandoning his own wife and children. In 1832 Eli and Eleanor moved to Red River County. Both filed land claims but Eli’s was complicated with the fact this was his second land claim, definitely not allowed by either the Mexican government or the soon-to-be new Republic of Texas.

Eli and Eleanor never married, although they were arrested and charged with adultery in Red River County. Both were separately found “ not guilty” by a jury. With numerous lawsuits, lost land claims, and snubs by neighbors, the couple lived there until 1848 when Eli went to Jefferson to build bridges. No one knows what happened to him but he completely disappeared. Eleanor moved to Greenville where her children lived about 1852. She involved herself in land transactions, of course, and was one of the original charter members of the First Baptist Church. Because she remained a widow, she was able under both Mexican and Republic of Texas laws to hold her own property. Before she died in 1861, she divided her property among the children she had with both Maxfield and Eli. Some of those descendants still live in Greenville.

Time and space are running out. Next week you will learn who the last three invitees to the Fantasy Dinner Party are.