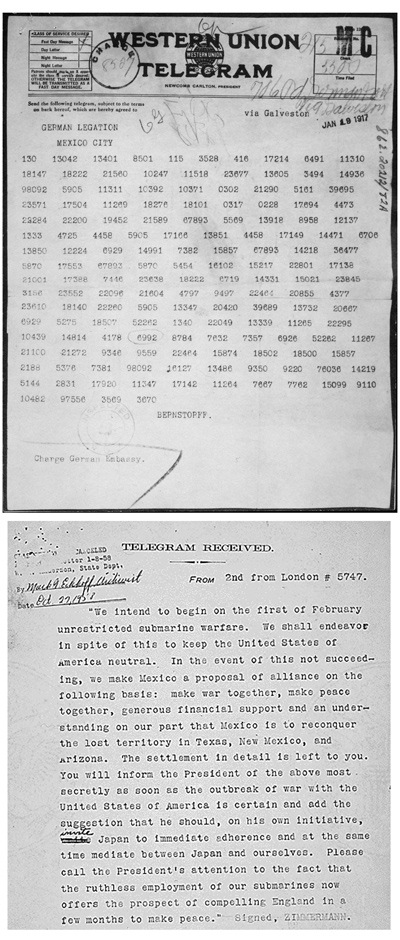

The Zimmermann telegram as it was first seen in Room 40 of the British Naval Intelligence Agency and below is the translated text.

One of the best authors to write about World War I was Barbara W. Tuchman. Her first book, the Pulitzer Prize winner The Guns of August set the stage for the beginning of the Great War. Later she wrote The Zimmermann Telegram to explain the United States’ entry in the war. Both are quality works, not only for academics, but also for the average citizen who wants to know how this war even occurred.

Tuchman graduated from Radcliffe College in 1933. She went to work for the American Council of the Institute of Pacific Relations, followed by a few years at the Nation, and later as a war correspondent in Valencia and Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. Henry Morgenthau, United States Ambassador to Turkey before the First World War was her grandfather.

Tuchman is said to have retired to a shed in her backyard while her daughters napped. It was there she wrote all of her books. Of course, she had a nanny for the girls, housekeepers and gardeners for her large Connecticut home, and the shed was probably not what we imagine. But she managed to produce ten works of non-fiction dealing with United States diplomacy in the first half of the twentieth century, two of which were Pulitzer Prize winners.

The Zimmermann Telegram is a fascinating read. The connection between German spies on the east coast, unsettled labor relations in the U. S., and the raids along the Texas-Mexican border are hard to believe but also very frightening. It puts today’s immigration issues in a frightening context.

Then there was President Woodrow Wilson who truly believed that it was his mission to end all wars. He ran on the campaign pledge in 1916 that he kept the U. S. out of the war and would continue to do so. Next, he tried to convince all major parties in the war to agree to peace without victory. Finally the contents of the Zimmermann Telegram, Congress and public opinion convinced Wilson that the United States must step into the fray.

Tuchman detailed to the best of her ability the British capability of decoding top-secret telegrams. The British Naval Intelligence obtained through sheer luck the codebook for German telegrams, which at that time were transmitted on public telegraphs. Most every countries changed their codes routinely; but not the Germans. Tuchman claimed they were too arrogant to imagine anyone could decode them.

All code work was done in Room 40 in which experts throughout the Empire worked night and day. A similar system was in place during World War II. Since Tuchman’s book was published in 1958, it seems amazing that such information was released during the Cold War.

I highly recommend The Guns of August and The Zimmermann Telegram. It was only 99 years ago that such events occurred. Each of her books gives the reader some insight into today’s political environment.