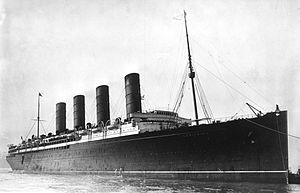

The Lusitania arriving in port. She was easily identified by her size and the four funnels only the Lusitania had. Despite her unique identity, Walther Schwieger of the U-20 wrote in his log he did not recognize her as he fired two torpedoes at the liner.

I recently read a fascinating book about the last crossing of the Lusitania. I suspect many have never heard of the ship and its impact on American entry into the Great War or World War I. The book, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, was published in 2015, and is by noted non-fiction author Erik Larson.

Larkin wrote in his introduction, “I give you the saga, and the myriad forces, large and achingly small, that converged one lovely day in May 1915 to produce a tragedy of monumental scale . . . “ The Lusitania was the pride of Cunard Line, the largest steam-ship sailing the seas in 1915.

Larkin is an exceptionally good author, presenting all points of view of the event simultaneously. The reader is never confused, though. In this book, Larkin relied on recorded interviews with survivors, diaries, books written by survivors and other historians, archival papers, and even the log of the U-20, the German U-boat that sank the star of the Cunard line.

There were actually three parties involved in the saga. First there was the ship itself, with a full component of passengers, crew, the captain, and even three German stowaways locked up in the brig below deck. Then there was the U-20, the German submarine on patrol around Great Britain. Walther Schwieger, the captain of the U-20 was not specifically looking for the Lusitania; he wanted to destroy the largest number of allied ships. The third group was an ultra-secret British intelligence unit in London who believed their findings were for the military eyes only.

In 1915 the United States was neutral, supposedly supplying only food, medicine, and clothing to civilians in Europe. Great Britain, France, and Russia saw the U. S. as a savior, the force that could break the impasse along the Western Front. But Woodrow Wilson was running for his second term on the platform he had saved us from the war. Winston Churchill, associated with the intelligence unit, believed there would be no Britain if the U. S. remained neutral much longer.

The morning the Lusitania set sail from New York, the German embassy placed an open letter to passengers, warning them of the danger of sailing across the Atlantic into Liverpool. Few passengers saw the warning, many of which were Americans. There was an aura of gaiety on the voyage. Children played on the deck, the weather was pleasant for the most part, and food and entertainment were delightful.

Captain William Thomas Turner falsely believed the ship would be escorted into harbor by British warships. Passengers also felt safe. But Germany was changing past strictures of warfare that kept civilian ships safe from attack.

I won’t divulge the details, but I can tell you it is a riveting account of a tragic event. One little secret – there were some survivors on the Lusitania.