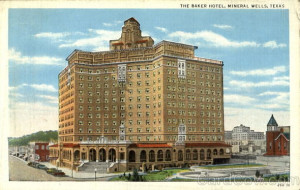

The Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells, Texas, was a popular spot for vacations from the 1890’s through World War I. (Photo courtesy of cardcow.com)

The Texas & Pacific Railway paid for a series of ads that ran in the Commerce Journal during March 1914. Railroads frequently offered excursion rates to events such as the State Fair of Texas, a Confederate Veterans Reunion in Nashville, or to the “Old States” during the Christmas season. But this particular ad was for an excursion to Mineral Wells, Texas, known as the “Human Repair Shop” according to the advertisement.

There have been several articles lately about the possible renovation of the Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells. The grand old lady sits in a prominent spot in the downtown of town. My aunt and uncle spent their honeymoon at the Baker in the 1940s. When I heard about it I thought it was rather unusual, but my aunt was somewhat eccentric.

To me, Mineral Wells was a dusty town south of my hometown of Jacksboro, the place where the boys in my class went to buy beer since Jacksboro was as dry as a bone. But as the ad explained, Mineral Wells was blessed with mineral waters, believed to cure anything that “ailed” you. I don’t know if the treatments worked since I never tried them. I have seen pamphlets and brochures celebrating the wonders of the waters. Mineral Wells was the go-to place from the 1890s to World War I. Actually, there was another hotel in Mineral Wells known as the Crazy Water Hotel. Needless to say, it’s not there anymore, having never been a top spot for the tourism committee.

After reading about two to three week excursions to Mineral Wells to partake of the baths, I began to contemplate pre-World War II vacations. Did our ancestors actually take long vacations, and if they did, what did they do? After the First World War, the automobile became an acceptable means of travel. It allowed individuals and families a more flexible itinerary than railroads did and to a certain extent was much cheaper.

Walworth Harrison took his mother and two female cousins on an automobile trip from Greenville to San Diego, up the Pacific coast to Vancouver, and home through Wyoming and Colorado in the summer of 1921. Harrison kept an incredible diary describing roads that were no more than cow paths, seeing women in shockingly clad in pants, and dealing with numerous mechanical breakdowns. The trip consumed more than six weeks.

We know about the journeys of the “Okies” during the Dust Bowl, but those could hardly be described as pleasure trips. Many families never made it to California where they would have been turned back at the border. They simply drove until the money ran out.

Throughout the 19th Century, excursions via rail were acceptable but seldom enjoyed by the average family. Even moving from Georgia to Texas was out of the question for most; it was simply too expensive. Sometimes local newspapers wrote that the more prominent and wealthier citizens went to New York on business, or to Atlanta to visit an ailing relative, or even that men took hunting trips to Mexico or Colorado.

I think I will pursue the idea of a vacation as it pertained to the ordinary farmer or wage-earning laborer before World War II. Something tells me it won’t be a lengthy paper.