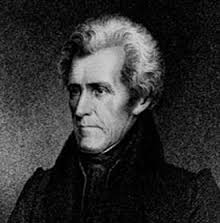

Andrew Jackson, 1767-1845, was one of the most popular American presidents in the South. Many parents named a son in his honor throughout the 19th century.

Some things change and others remain forever. Naming patterns can be like that. During the 19th century, it was quite common to name a son James Monroe, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison or Andrew Jackson. By the last quarter of the century males were named Jefferson Davis, Billy Sherman, Wade Hampton and especially Robert Lee. By looking at a son’s name, it was pretty safe to determine the father’s politics. Sometimes though given names were shortened to initials only.

Such is the case of two men I have researched. Both went by A. J. Being a Southern historian, I assumed both men were named for the populist president Andrew Jackson. I was right on one count but entirely off on the other. How did I learn what the initials meant? I looked at every piece of paper, or a digitized copy, until I found some clues.

With Andrew Jackson, I found him listed as Jack, Jackson, and A. J. As a child he was called Andrew a name that has been handed down in the family for generations. Now President Jackson was not popular in the north, mainly because of his treatment of Native Americans and holding slaves. But our man was born in Arkansas prior to the Civil War.

This man was a very interesting character. He married Martha E. Mitchell before the 1870 Census. She died in 1878 leaving her husband to care for four very young children. He soon married her sister Mary. Sometime in the next ten years, the entire family moved to Texas where Mary Mitchell died leaving more children.

On September 1891, this farmer whose given names we know were Andrew Jackson, married another Mary some twenty years younger than he was. Eight years later A. J.’s son named after President James Monroe married the younger sister of A. J.’s third wife.

Confusing? Definitely. Uncommon? No! Death rates were much higher in the 19th century than they are today. Men who were farming were not able to care for young children and work the fields. So the solution was to either hire a nanny to live in the home (only to have the neighbors eyebrows go through the ceiling) and care for the family or marry a younger woman who would provide for their needs. In both cases, our A. J. married someone he and his children knew well. The third wife Mary was the daughter of a neighbor. The fact that his son married her sister confirms that there was a close relationship between families.

Another factor to consider is found in new statistics released by Civil War historians who estimate that as many as 750,000 men were killed or died during or shortly after the war. Husbands were in short supply.

Women also found themselves in a bind when their husbands died. Not only were they left with the same farm issues, but also employment for women was extremely limited. Marriage to a widower was often not ideal; it was based on necessity.

But what about the other A. J.? He turned out to be Arthur Jasper and was another character. However, space is running out. Arthur Jasper’s story must wait for another day.