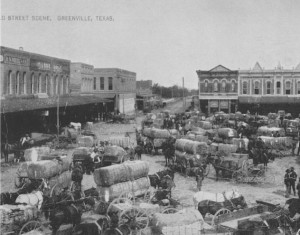

The Public Square in Greenville, Texas, ca. 1882. Farmers brought their cotton to town to sell each fall. If a street buyer, dressed in a suit, had his foot on the spokes of a wagon wheel, everyone knew the load was mortgaged to a furnishing merchant as crop lien.

On December 16, 1914 more than 200 farmers from North, East, West, and Central Texas gathered in Greenville for the Northeast Texas District Convention of the Farmers Union. It was an extremely critical time for them. With the war raging in Europe, there were no markets for their one cash crop: cotton. European mills that had previously bought cotton from the Southern states were now converted to armament and ammunition plants.

Over the years, farmers in the South had planted only cotton, relying on other areas of the U. S. for food and various necessities. On many farms, cotton was grown right up to the house, leaving no room for a small garden, a few hens, or even a milk cow. Weather, soil conditions, and market prices fluctuated drastically. The vast majority of farmers relied on crop lien and furnishing merchants.

Jim Bissett in his book Agrarian Socialism in America: Marx, Jefferson, and Jesus in the Oklahoma Countryside 1904-1920 offered an excellent vignette to describe the plight of the American cotton farmer. “Upon arriving in town with his harvest, the farmer first looked for a buyer who would pay a reasonable price for his cotton. At harvest time, streets were crowded with farmers in wagons loaded with cotton, and a class of men known as “street buyers” who brought buyers and sellers together. The street buyers were in the employ of local “furnishing” merchants. They walked from wagon to wagon naming the price each farmer would receive for his crop. No bartering was allowed, no fair market price was offered. Some farmers rejected the buyers’ early offers but quickly learned how limited their options were, and soon agreed to an even lower price.

“After selling his cotton, the farmer had to purchase supplies; inevitably from the same merchant who employed the street buyers. But did he receive a quote in line with the price he sold his cotton for? NO, he was told that the price of staples and agricultural supplies had gone up. He could pay or go home empty-handed. The commercial agricultural system was explicitly designed to give full advantage to the furnishing merchants at the expense of the farmer.

Cotton was a cash crop; the farmer was not paid until he sold his bales. That was all the cash he received each year. The rest of the year, anything he purchased was bought on credit. Cotton was simply the collateral locking the farmer into never-ending debt. No laws governed interest charged on credit at the store.

Any farmer felt fortunate to receive enough cash to pay off his debt and begin the next season with a clean slate. By 1914 some annual interest rates rose to 75 percent on necessities purchased at credit stores. Even worse, the credit stores charged as much as 50 percent more for credit than for cash sales non-agricultural patrons made.

Today most people think of King Cotton, but a king can quickly become a dictator. In the early twentieth century, Bisset tells us that furnishing merchants became dictators of farm production. They believed that the only crop worth growing was cotton.