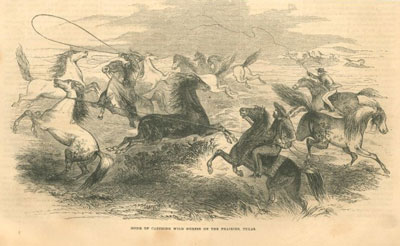

The first Anglo settlers in Hunt County realized that the best product of their new land was not cotton, but cattle, sheep, and horses. All three had multiple tributes that included hides and food. To add to the choice was the abundance of wild horses found around the area where Cow Leach Creek merged with Caddo Creek. Some early settlers bred those wild horses with their donkeys to produce mules, a huge animal through out the South.

Cotton became profitable once transportation was available, but without buyers, cotton was useless in 1840 when the early settlers arrived. The rich prairie lands and wooded creek bottoms provided an almost ideal setting for cattle, sheep and horses.

One old-timer wrote “great natural meadows covered with green grass thrown into undulations by gentle breezes, relieved and beautified by flowers from the modest iris and blue daisy to the brilliant plume.”

Livestock grazed on inexpensive native grasses almost all year long. Stock raising was surprisingly the principal employment for most settlers. In fact, one old-timer observed that “a person’s wealth was measured by the number of horses, cattle, and sheep he owned. Lands were almost worthless; no one had money to buy any. Stock kept in good condition the year around. I have never seen fine fat beef killed in the midst of winter never having been fed. No one thought of putting up food except for work stock. In cold, rainy, bad weather, which seldom came, stock sought shelter in the thickets and creek bottoms.”

Usually in the spring, stockmen would round up several steers and drive them east to Shreveport or as far as New Orleans. Sometimes they headed them north at the end of the railroad in Kansas to sell them. One tale says that a group of young men took steers to Leavenworth, Kansas to sell. They drove the cattle through rainstorms, flooded rivers and Indians wanting fees to cross their land. The young men made it safely to Parsons, Kansas, where like many young men they bought new clothes after the long drive.

Not many people realize that sheep also thrived in Hunt County. In the 1860 Census sheep actually outnumbered horses and cattle. That year tax rolls reported 11,057 sheep in the county, which averaged 27 per farm, though only 4,458 horses and 299 mules were reported.

One woman who lived in the northeast part of the county recalled “we had lots of sheep and would shear them twice a year, in May and October. Then we would card and spin the wool and knit out socks and stockings. Some would even weave the wool into cloth.”

The importance of stock raising was the result of lack of improved land and lack of inexpensive transportation. Lack of railroads, navigable rivers and good roads further inhibited the development of commercial farmers, particularly cultivation of cotton, since farmers simply had no practical, inexpensive way of getting bales of cotton to the market.

In the 1880s, the coming of the railroads and the wide use of barbed wire made cotton production more profitable and stock raising took a back seat.