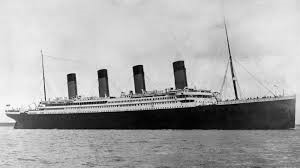

To paraphrase Charles Dickens’s beginning of A Tale of Two Cities, 1912 was also the best of times and the worst of times. One of the most tragic events occurred around midnight on April 12 when the new, luxury ocean liner collided with an iceberg and within four hours was at the bottom of the North Atlantic. The Titanic was the wonder of the new technological and industrial age. Owned by the White Star Ship line, it embarked from Southampton on April 10, 1912 in full regalia for the wealthiest Americans and Europeans. However, in the lowest part of the Titanic were a large number of men, women and children bound for the United States and a better life.

The Titanic was 882 feet long with seven decks, a state-of-the-art gymnasium, swimming pool, Turkish sauna, three elevators and a post office. There were three passenger classes, first class for the wealthy elite, second class and steerage, those coming to America a new life. Each class was surrounded by a locked barrier. First class had nine course dinners, second class were served standard courses, while steerage had simple but nourishing meals.

Cost of sailing on first class with a private deck was $4350 for six days. That would be $116,672.75 in 2019.

The ship had a capacity for 2566 passengers and 892 crew members, and all were filled. Maritime laws required 20 lifeboats that would carry only 1178 person in time of danger. Just before the ship set sail, some of the lifeboats were removed to make room for more recreation on the upper deck. As they sailed out of the harbor at Southampton, the Titanic narrowly missed clipping the USS New York.

At 11:40 PM on April 14th, the Titanic collided with a large iceberg. Two hours and 40 minutes later the ship was completely lost. Wireless operators were either too busy or too sleepy to send out warnings. The captain and crew had only a few days to take the large ship out for sea trials. Some researchers dismiss the theory that the iceberg cut a large hole in the ship; instead they believe the damage to the hull was mostly small holes caused by popped rivets creating little impact.

The tragedy, the huge number of people involved, the lack of adequate lifeboats all led to various erroneous information concerning the event. As the ship went down, the orchestra played to keep up spirits and prevent panic. As women and children waited to get on a lifeboat, a group of armed men from steerage tried to take the lifeboat, but crew members stopped them.

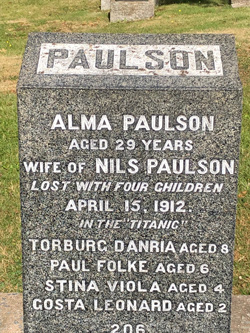

The nearest major port was Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Carpathia was the first ship to arrive at the scene. Arminias Wiseman, on the Mackay-Bennett, a small ship with crew members who repaired underwater telegraph cables between Europe and North America, remembered that “as far as the eye could see, the ocean was strewn with wreckage and debris, with bodies bobbing up and down in the cold sea.” That ship carried 100 coffins, tons of ice, an undertaker, and a chaplain. Three hundred six bodies were removed in the initial search. Persons identified as first-class passengers were placed in coffins to receive a Maritime burial. Others were brought to Halifax on the Mackay-Bennett and two other vessels. Embalmers from all over the Maritime Provinces came to help with the deceased. Those whose bodies were recognized were sent home for burial. The remaining bodies were buried in three cemeteries in Halifax.

There are no official numbers. Between 1250 and 1502 bodies were found. It wasn’t long before changes were made for maritime traffic. Net safety regulations, regular safety drills, and a re-examination of wireless service in ocean safety. The International Ice Patrol, created at the time, is still in existence today.