This year March roared in like an angry lion. Gray clouds and roaring winds caused some power outages. But it set the stage for a wonderful spring when the weather will be like a lamb before the end of the month, we hope.

Here in northeast Texas we can expect storms for the next two or three months, maybe lots of rain, but the pop-up greenery of trees, flowers, and grass will delight us. March is notorious for its wind; wind like we find throughout the Great Plains, from Canada to South Texas. The wind and cold weather stopped early settlers; they skipped over the plains and mountains heading for the West Coast and gold. By the end of the Civil War, farmers and cattle men realized the wonderful soil in the region. Cattle grazed before tractors plowed the fertile soil that created dust storms, the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, and loss of that wonderful farmland.

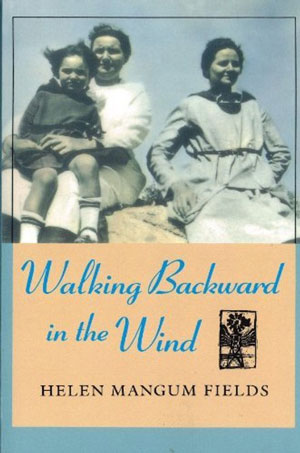

Helen Mangum Fields wrote about her childhood on the Great Plains. Her writing is an amazing description of that part of Texas before the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression when farmers prayed for rain at the right time and watched for ominous storms. Fields takes the reader through a whole year of her life on a small farm close to Ragtown in Garza County. A school from first through sixth grade, two churches, a couple of stores, and the post-office were the entire Ragtown. Storekeepers and teachers made up the population since everyone else lived in a four-square home built for them by C. W. Post, best known for cereal, but also involved in real estate, especially in West Texas.

Garza County is on the edge of the Caprock, the flat part of Texas. Fields gives very little information about the farming and housing arrangements. She stated briefly that she lived with Auntie and Uncle since she was a baby. Perhaps war, influenza, or any other disaster took her parents. Yet, she loved her family, her home and school, even though she had no siblings.

Fields gives a clear picture of life on the Caprock, where farming was the sole occupation. There was no running water, no insulation in the home, no radio, television, or internet. Refrigerators were unheard of, although Uncle bought an “ice box” at one point. Uncle drove her two miles each way every school day. She gathered eggs, also hating it like I did, helped to feed the small animals and worked with Auntie, her grandmother and another aunt in the kitchen. School was for learning, with two grades in one classroom. Everyone brought their lunch.

Summers were the most entertaining part of the year. Church revivals, picnics, visits to and from neighbors, and canning produce from the garden filled the days. It was also the time for hard work on the farm, chopping cotton, weeding the garden, taking care of baby calves, chickens, and hogs. Fields accepted the chores as part of life in West Texas and never complained.

Thanksgiving and Christmas were the big holidays. With no television, toys did not appear until just a week or two before Santa came. Valentines cards were made at school, nothing store bought. When school closed in May, it was a time for plays and programs and good-byes until Labor Day.

Helen Mangum Fields titled her book Walking Backward in the Wind. According to Fields a “West Texas child in the ‘20s pulled his cap more closely over his ears, buttoned his coat securely and waited for that special harbinger of spring, the bone-shattering thrust of the first sandstorm to knock him off his feet.”