Every election year we hear a great deal about the U. S. Constitution. Should it be changed, is it fluid, or is it carved in stone never to be altered?

This column will not touch those topics but uncover a huge secret. In 1917 Texans voted for or against Prohibition as did the rest of the United States. But technically it didn’t matter. In 1876 Texas men voted to accept another Texas constitution. (Remember, women could not vote until 1919.) The 1876 constitution had a local option clause where communities could determine the wet or dry statue.

From then until 1917 there were numerous, or maybe countless, wet/dry elections in the state. Religious beliefs, cultural traditions, and plain old orneriness influenced the votes. Catholic churches and Jewish synagogues used wine in their services. Hispanic men supported the wets as did city residents in places like Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas/Fort Worth. African Americans in East Texas tended to vote wet. So that leaves a big chunk of the state with strong opposition to any kind of alcohol.

Imagine a line along Interstate 20 from the Louisiana border to New Mexico. Now think about the people who resided north of that line. That’s where the orneriness comes in. It was a sparsely populated area with families involved in various types of agriculture, from cattle and horses to timber and cotton. Family traditions and Protestant beliefs molded their politics. While it was okay for males to take a snort of whiskey every day or so, women were considered so dainty and fragile that not a drop of whiskey should ever touch their lips.

Guess how that part of the state voted in every election? At the early elections when votes were close the wets passed by a slim margin. In fact, at one point a woman’s club offered to campaign for dry votes and were turned down. After all, women were women and had no reason to be involved in such masculine issues. Gradually women gained more and more clout, especially with the surge of women’s clubs and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

Looking at petitions in the Texas State Archives submitted here in Greenville and Hunt County between 1880 and 1910, women signed petitions, some on the line below their husbands but with Mrs. to identify them as married while others used a given name without a husband’s name nearby. Or maybe she was a widow or unmarried woman.

In Greenville dry voters won the contest in 1903. But not without a slight rebellion. All around the courthouse there were saloons, grog houses, and hotels where liquor flowed freely. On the northwest corner of the square was a saloon that sold groceries. Women used a door facing Lee Street to enter or sent their maids to shop. The biggest, most elaborate saloon was the House of Lords. Supposedly Carry Nation visited that watering hole and left her mark. On the south side of the Square was a saloon owned by one of the Shields brothers, one of the four brothers of exceptional height who traveled with the circus for several years.

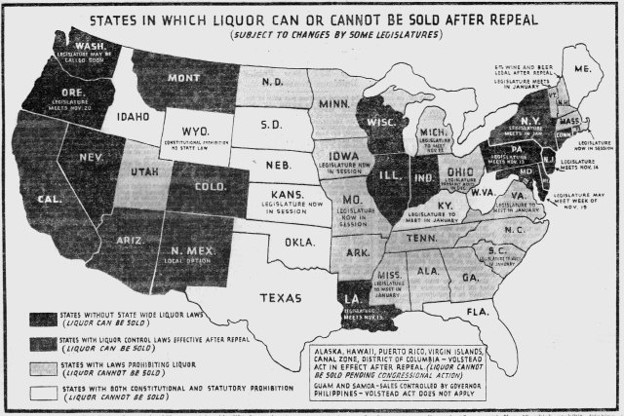

The group of saloon owners tried to defy the vote. They petitioned the District Court under Judge A. P. Dohoney of Paris, a strong supporter of prohibition. Needless to say, their petition was not accepted, and Greenville went dry. When the 18th Amendment supporting Prohibition was repealed in 1932, the vote for repeal was not necessary. Greenville and Hunt County were dry and stayed that way for many, many years.