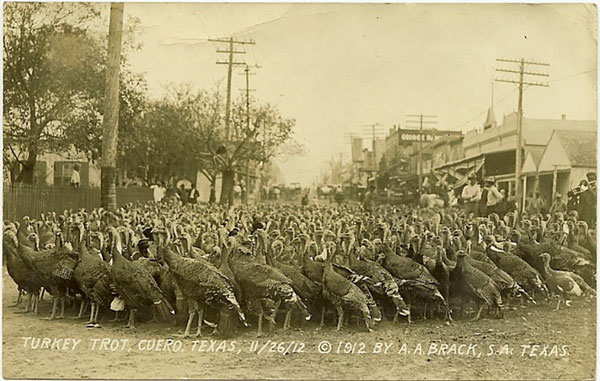

Cowboys walked cattle to markets for ages, but did you know that farmers walked turkeys to markets also? In November 1918, farmer W. E. Riddle of the village of Bryson drove 178 turkeys to the Jack County seat in Jacksboro. There he sold his rafter of turkeys to Phillips and Gafford for a nice sum of $417.96. One hundred years later that would amount to $6,472.97. The walk was a mere twelve to fifteen miles, and probably completed in one day.

So how did Mr. Riddle accomplish this feat? I understand turkeys are fairly easy to corral on a walk with a knowledgeable drover, sometimes with a little guidance in the form of a cane-fishing pole, but are generally amiable fowl.

Turkey walks began in the 16th century when European explorers sent wild turkeys home. There farmers developed them into a domesticated farm fowl, only to be re-introduced in North America by the 18th century. That was when turkey walks became common events in November.

Some rafters of turkey contained more than 1,000 birds on voyages of more than hundreds of miles. Predators often thinned out the herd, bigger birds occasionally trampled some, and herders or children scattered kernels of corn to keep the birds together. If the trek was long, someone drove a covered wagon filled with shelled corn. A small hole was drilled in the bed of the wagon so the kernels could fall on the ground to encourage the rafter to follow. One or two more boys walked along to supervise the birds. Along the way, turkeys strayed from the group to forage on grasshoppers and other insects, in a similar way that cattle foraged on cattle drives.

At the first sign of sundown, turkeys head to higher ground, in trees, on tops of building, or other such places to roost. Turkeys have fairly hefty bodies. Sometimes, too many in a tree or on a shed caused their roosts to fall. Seldom were turkeys injured; they simply flew back to the ground. On long drives, dogs safeguarded the rafter from predators.

We still have native or wild turkeys in parts of Texas. They are beautiful birds and quite welcome, as they love to devour pesky insects.

In the early two decades of the 20th century in north Texas, farmwomen began raising turkeys. I know one woman who was very refined and elegant that raised turkeys. I’m not certain how she sent them to market but I wouldn’t be surprised if she didn’t walk them to town with the help of her two sons. Her husband let her have the profits from the enterprise. One time she went into the local jewelry store and bought a lovely set of china. Mrs. King believed in elegance, even on the Texas prairies.

Here are a few tidbits for you to share at Thanksgiving Dinner tomorrow. Turkeys group in rafters, a nest full of turkey eggs is called a clutch. The female is a hen and the male is a tom; only toms gobble. That red fleshy thing dangling from the tom’s neck is a wattle. I know not why he has one. Finally, Big Bird’s costume is made of dyed turkey feathers. Most turkeys have more than 300 feathers.

Enjoy your Thanksgiving turkey!