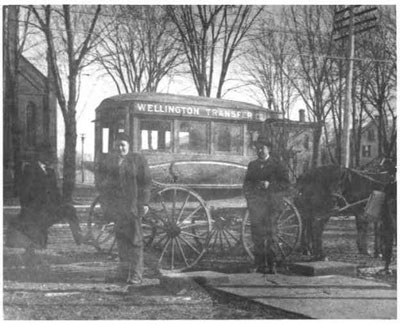

A later version of the hack that Alfred T. Howell rode from Shreveport to Clarksville, Texas in 1852. Undated image of a Wellington Transfer Co. horse-drawn coach, also known as a “hack.” Photo 970300 of “Wellington Family Album” Collection, Herrick Memorial Library. Permission to display generously granted by the library.

Alfred Thomas Howell is a historian’s dreams come true. A Virginia native who studied law in Kentucky before a daring move to the new State of Texas in 1852. Trained as an attorney, Howell conscientiously wrote letters home to family in Richmond for more than ten years. Each one gives a unique insight to the early days in Northeast Texas.

On February 29, 1852, Howell arrived in Shreveport after a pleasant trip from New Orleans aboard a steamboat on the Mississippi and the Red Rivers. Arriving at Shreveport, Howell noted that few stores in the town closed on Sunday morning. That concerned the son of a Baptist preacher, especially when he realized most men were either trading horses or mules. Others were loading or unloading steamboats. Howell was in for a surprise on the Texas frontier.

To get from Shreveport to Clarksville, Howell’s final destination, he had to choose between three options. Wait for the next steamboat to Kiamatia and who knew when the water would be high enough to make the voyage. Buy a horse or a mule and try to find the county seat of Red River County. Or he could hire a hack for twenty-five dollars. He chose the latter. The hack was a long, round-topped carryall pulled by three horses. The first day one of the horses died, leaving two rather poor horses to pull the hack over what Howell referred to as the “desperate nature of roads.”

So the adventure began. Howell claimed they traveled through the poorest portion of Texas; probably the reason early Texas historians ignored the Red River settlements. The pine country reminded him of the pine forests in the eastern sections of North Carolina and South Carolina. Along the way the thinly settled region sported newly built log cabins along the road. Howell stated they were occupied by squatters but gave no reason for such assumption. Horses mired in the muddy swamps about 400-500 yards long. Travel was at a snail’s pace, especially when having to pull one or the other horse out of the mire. Howell and other passengers worked along side the teamsters. Howell wrote he was tired of the difficult travel conditions he experienced.

At first only a few prairies appeared. As the road continued into more open prairies game became plentiful. Wild geese constantly flew overhead. Thousands of wild ducks, deer, bears, and other wild life were plentiful. Venison was served every meal, never quite to Howell’s taste.

Several of the families in Red River County were from Virginia and were acquainted with the Reverend Howell and his wife. Invitations were offered to their son who visited and enjoyed their hospitality. One of the men he met was Charles H. Peabody, a jeweler who planned to open a shop in every town within a 150-mile radius. Peabody was probably successful as he was the only jeweler in all of Northeast Texas.

Alfred T. Howell continued to write his weekly letters, with outlandish excuses of not setting up a law practice and his subsequent large expenses and debts. Often he seemed to focus more on the negative side of frontier life. However, without his letters this chapter of Texas history would be lost.