Americans love their first amendment rights. Look at opinion pages in newspapers, listen to nightly news on more than one television channel, or simply open up social media. Even having a meal with a few persons reveals how important we value the right to express ourselves.

Americans love their first amendment rights. Look at opinion pages in newspapers, listen to nightly news on more than one television channel, or simply open up social media. Even having a meal with a few persons reveals how important we value the right to express ourselves.

Such has not always been the case. Within days of the American declaration of war on Germany in April 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917. Citizens who opposed World War I, and there were many Americans who did, found themselves legally silenced, but voiced their displeasure with riots and strikes.

The Act was primarily aimed at military security. It prohibited interference with military operations and recruitments. No one could picket recruitment sites or march at the gates of a military or naval base. It also prevented insubordination in the military. Enlisted men, officers, and civilian employees quickly learned to keep their dissatisfaction to themselves.

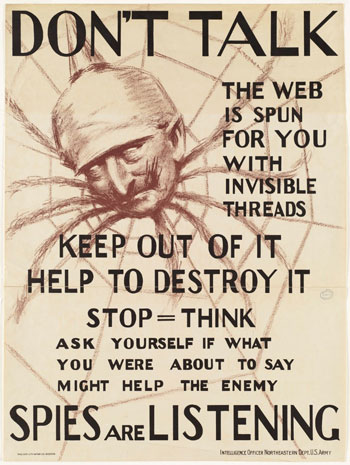

More importantly, it attempted to prevent support of United States enemies during wartime. As early as 1913, German agents arrived in American to cause chaos in factories, initiate strikes among transportation workers, and set up an elaborate web of spies. It was surprisingly successful because the numerous Germans who had been sent here were very fluent in English. They fitted well into any American group. After the declaration of war many returned to Germany.

Along with the Espionage Act was the Trading with Enemy Act. The United States was purportedly a neutral nation, but sent arms and ammunition to the Allies, France and England. American banks loaned funds to finance the Allies. Food and supplies from America fed starvation stricken Belgium, also neutral. The Trading with Enemy Act disallowed any trade with Germany once war was declared here in the U.S.

President Woodrow Wilson really wanted to censor all newspapers. Congress disagreed. However, print materials were shipped through the US Post Office. Any materials that could be considered a violation of the Espionage Act would be blocked. The whole country was filled with a nationwide network of investigators looking for intimidating mail.

Once the United States was actively involved in the Great War, the country enacted a set of amendments to the Espionage Act known as the Sedition Act of 1918. It prohibited many forms of speech aimed at negative statements about the government, war efforts, or the sale of government bonds. If found guilty, the party usually received a five to twenty year sentence. It increased the power of the Postmaster General by allowing him to refuse to deliver mail that met punishable speech criteria.

The Sedition Act was repealed in 1920 but the Espionage Act of 1917 was left intact and has been contested in the Supreme Court ever since but never repealed.