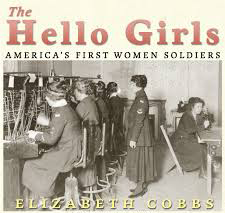

Only six women, working three at a time in 12-hour shifts, keep Pershing’s headquarters connected with the rest of the Army during the Battle of St. Mihiel. Helmets and gas masks hang from their chairs. Left to right: Berthe Hunt, Tootsie Fresnel, and Grace Banker. (Courtesy National Archives)

World War I was a venue for new experiments, new methods of doing things and new inventions such as wristwatches, daylight savings time, and using telephones for communication between supply depots and military commands. The use of telephones is one of those little secrets that only recently came to light.

General John “Black Jack” Pershing of the American Expeditionary Forces believed that good communication was extremely important, especially between Great Britain, France and the United States. Besides, men did not have the dexterity that women had using complicated switchboards and were needed more in the field. When a call went out for female telephone operators, some 700 American women volunteered. It was then that Pershing and the United States Army Signal Corps realized the operators must be fluent in both English and French.

By the summer of 1917, two hundred twenty-three young women who were already employed by Bell Telephone Company began taking physical training, enduring medical exams and inoculations, and took the Army oath. They wore regulation uniforms including the identity disc, the forerunner of dog tags. They agreed to follow strict military protocol, were subject to court-martial and often only a few miles from the front lines in the height of battle.

The women arrived at Brest, France, ahead of most doughboys. As quickly as the Corps of Engineers ran the ever-shifting networks of telephone lines across France, the Hello Girls, as they became known, were busy. General Pershing congratulated the young women on their jobs, later calling them a significant factor in winning the war. Hello Girls not only connected phone calls but also often stayed on the line to translate between the three armies.

After Armistice Day on November 11, 1918 many Hello Girls stayed in France to assist in making arrangement to get troops home. Some remained to translate for representatives at the Treaty of Versailles. The last of the Hello Girls returned to the U. S. in 1920. Their ability to function under pressure in complicated tasks has been tied to the success of the suffrage movement in the United States.

However, when they returned home they were in for a jolting surprise. The Hello Girls realized they were high-paid civilians who were known for their bravery and resourcefulness, but not veterans. They were eligible for no benefits, simply because they were women. No benefits, no medical care, no commendation, or honorable discharges. The Hello Girls did not have the right to wear their uniforms. There would be no military funerals.

What happened? Whether intentional or accidental, when General Pershing wrote up articles of military service for the women of the United States Army Signal Corps, the word male was present, as in male soldier. The Marine Corps and Navy had inserted Yeomanettes in their articles. It would take years of petitioning Congress for the Hello Girls to garner their rights. It was 1977 before President Carter signed an order granting full veterans status to the few survivors.

In her book, The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers, Elizabeth Cobbs blames “stubborn pride, bureaucratic arrogance, and belief that women simply did not recompense blinded senior staff officers to faceless female veterans.”

In her book, The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers, Elizabeth Cobbs blames “stubborn pride, bureaucratic arrogance, and belief that women simply did not recompense blinded senior staff officers to faceless female veterans.”