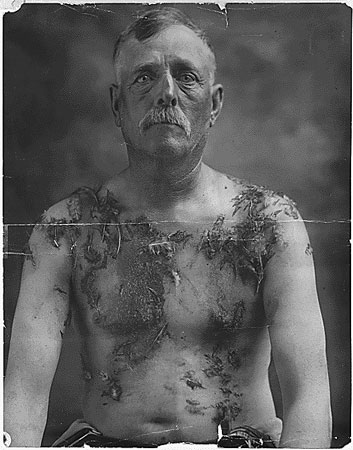

This photograph records the plight of German-American farmer John Meints, who was tarred and feathered on the night of August 19, 1918 in Luverne, Minn., under suspicion of being insufficiently loyal to the United States. He had refused to participate in a war bond drive to his neighbors’ satisfaction. (National Archives, Records of the District Courts of the United States.)

Tar and feathers, that’s what they did during the American Revolution, wasn’t it? A ghastly ordeal for the recipient, to say the least. But didn’t we as Americans become more civilized as our country grew? If you thought we ceased to submit a victim to such pain, you are sadly mistaken. Tar and feathers came back with a vengeance during World War I.

It is somewhat complicated for someone in the 21st century to understand. The federal government did not allocate millions of dollars to assist and then join the war with our allies, France, Great Britain, and off and on with Russia and Italy. Private citizens sent most of the food, clothing, canned milk and other necessities to war-ravaged Europe, from the onset in August 1914. When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the vast majority of funding came from Liberty Bonds.

Citizens were challenged or coerced, some might say, to buy Liberty Bonds. If they really could not financially purchase a bond, then they were expected to buy Liberty Stamps until they had enough to trade in for a Liberty Bond. The Red Cross was also soliciting funds to help care for wounded soldiers, citizens with influenza, and other catastrophes at the same time. Most Americans complied, especially in areas with few, if any German or other Eastern European immigrants. But many of many of those immigrants, their families, and certain religious groups refused to buy Liberty Bonds.

Wartime is a traumatic time for all citizens, whether supporters or adversaries. The Wilson Administration encouraged neighbors to spy on neighbors. Rumors were rampant.

When groups refused to buy the Liberty Bonds, even if they supported the Red Cross, they were seen as enemies to the United States. Some may have been, but most simply believed strongly in the First Amendment rights and believed they had the right to say no. That’s where tar and feathers entered the picture.

An example of early persecution of persons not supporting the war occurred in Brenham, Texas in late December 1917. Six farmers, all of German descent, who refused to join the Red Cross were taken from their wagons and flogged by a committee of the most prominent citizens of Brenham. No masks or hoods were worn in the incident during broad daylight.

In Kansas one citizen and two preachers were tarred and feathered for not supporting Liberty Bonds. One night in a rural Michigan community seventy-five persons drove to an isolated farmhouse. While the men bound the husband, twenty women tarred and feathered the wife for making hostile comments about the war.

Catholic priest Father Joseph Keller arrived in Slaton, Texas at the wrong time. The German native began his calling a few days after the entry of the United States into World War I. Father Keller was unable to make the sum the County Councils of Defense set for his Liberty Bonds. This issue was worked out but left many in Slaton suspicious of Keller. When Keller announced the church was expanding and planned to open a school in 1920, Protestant protestors felt it was time to teach the priest a lesson. Led by Baptist minister John P. Hardesty and state representative Roy Baldwin, a group of assailants forced their way into the rectory, tied the priest and dragged him to a waiting car.

Several miles from town where no one could hear the screams, the assailants removed the priest’s clothing, gave his twenty strokes with a leather belt before pouring hot tar on his head and back. Immediately they ripped open a feather pillow and spread the contents on the hot tar. At that point the assailants drove off leaving Father Keller to make his way back to Slaton. A local doctor removed the tar, a process that also removed the top layers of skin. He put Father Keller on the train to St. Anthony’s Hospital in Amarillo for further treatment. From there he went to Dallas to recover before joining the Diocese in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he died in 1939. Doctors believed the torture speeded his death.

In the 1920s state legislatures began to enact laws abolishing such horrific torture.