Important reminder

For the flu season

“Ka-chew,” said Lew to Miss Sue.

“Ka-chew,” was the answer to Lew.

‘Twas a sneeze and a squeeze,

And a squeeze and a sneeze,

For Sue, and Lew, too, had the flu.

It’s time to get flu shots.

Call your doctor!(Complements of the late Otis C. Spencer, author of Cow Hill “Bits & Pieces”, An Irreverent History of Commerce and Its People, Volume One.

Professor Mayo, the man who made the college great, died in 1917, hours before the realization of his dream of his college becoming a state institution. Mrs. Mayo, died in October 1918, seven months after a second marriage to her private secretary, J. L. Booth. Mr. Mayo is buried on the campus and Etta Booth Mayo Booth is buried at Rosemound Cemetery. (And no, I have no idea why Etta had the word Booth in her name twice. Something worth looking into. She was a fascinating woman)

Otis Spencer was a wonderful teacher, historian and friend. Along with Maude Johnson and Dorothy Moore, the trio collected a great amount of information about our neighbors to the northeast. Their motto was that history has been defined as a set of socially-agreed on facts. One of Dr. Spencer’s history teachers told his classes that after an interesting story, “If that was not true, it should have been.”

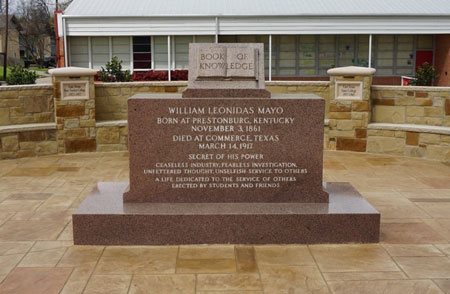

As mentioned above, Mr. Mayo was buried under a red granite monument, behind Henderson Hall, that marks his grave. Dr. Spencer told an unusual story about the burial of Mayo. When he died, Mrs. Mayo requested that he be buried on the campus and she wanted to make sure that he would never be moved. So, she hired William J. McKittrick, Commerce’s concrete paver, to pour concrete over the Mayo coffin before the grave was filled with dirt.

During the solemn graveside ceremony for Mr. Mayo, Mr. McKittrick’s machine could be heard in the background mixing concrete, a disturbing overture to the long Mayo eulogies. Finally, when the ceremony was over and the crowd disbursed, Mr. McKittrick walked over and yelled down into the open grave. “Mr. Mayo, if you are ever going to come out, come out now. I am going to cover you with concrete.” Then the grave was filled with dirt and “Professor” William L. Mayo continues to rest on the campus.

Later, students and alumni decided to build a monument to Mr. Mayo. Over several years, the group collected $3,455.60, contributed by 282 individuals. The red granite monument was dedicated on June 25, 1926 and stands today as a campus landmark. For many years, the “Mayo’s Ex’es” students who went to school under Mr. Mayo, held their homecoming reunion at the Mayo gravesite, until their last reunion in 1984.

You ask, “Why was Mr. Mayo not addressed as Dr. Mayo?” The simple answer was he didn’t hold a PhD. He was a simple teacher who had a school in Bonham. When it burned and the citizens of Bonham were not enthusiastic to pay for a new structure, Mayo came to Commerce where the residents welcomed him. PhDs in northeast Texas came later.