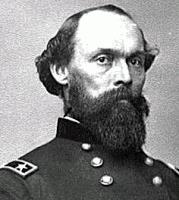

General Gordon Granger, USA, delivered the Emancipation Proclamation to Texans on June 19, 1863 on the lawn at Ashton Villa in Galveston, Texas.

One hundred forty-nine years ago last week General Gordon Granger and his Union troops landed at Galveston, bringing glorious news for some and disastrous news for other residents on the island. Immediately after landing, Granger read General Orders # 3 to the gathering crowd. An important section declared, “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.”

The day became known as Juneteenth to countless Texans and other Americans. More than two and one-half years earlier President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation as an Executive Order. Realizing that Texans would never accept the Proclamation without military force, the announcement was delayed until after the Civil War and Union occupation of the Lone Star State.

Ironically, most slaveholders in the Houston-Galveston area were well aware of the Executive Order. Newspapers from other parts of the Confederacy were smuggled into the port and published in the Galveston Daily News, printed in nearby Houston. The subject was discussed in hushed voices and debated in the local newspapers. Yet the recipients of the glad news were supposedly unaware.

Surprisingly, while the citizens of Galveston erected a statue of General Granger on the exact spot where he read General Orders #3, no Texas Historical Marker was placed there to interpret the event. Yesterday, such a marker was unveiled in one of the most historically conscientious city in the state.

News of General Gordon’s announcement spread like wildfire across the state. On July 14, 1865, Clarksville Standard newspaper editor Charles DeMorse railed publically about the illegitimacy of such actions. Congress was not consulted. The Southern states, that had voluntarily chosen to leave the Union, had no chance to vote on such a monumental decision. Similar arguments were heard throughout the state during the summer and fall of 1865. No one seemed to appreciate the foolishness of the arguments.

While the news spread rapidly, willingness to obey General Orders #3 was not so fast. Much of Texas, especially the Northeastern portion, was engulfed with war-like conditions. Rebellious southerners laid siege to Sulphur Springs, countless former slaves, Union sympathizers, and Union soldiers were murdered. It would be more than five years later before residents of this area felt safe to leave their homes. The War of Reconstruction was as destructive here as the Civil War had been in other areas of the South. Yet few know of the absolute pillage and murder that abounded.

For more information about this time period, you might want to read The Devil’s Triangle: Ben Bickerstaff, Northeast Texans and the War of Reconstruction by James Smallwood, Ken Howell, and Carol Taylor. Copies can be found in the W. Walworth Harrison Public Library and purchased at the American Cotton Museum. They can also be ordered through the East Texas Historical Association by calling 936-468-2407.