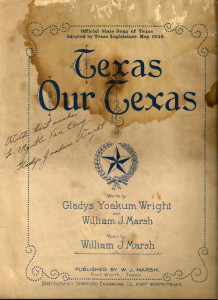

Autographed copy of the original sheet music to Texas, Our Texas. Changes were made to the lyrics when Alaska was admitted to the Union. Texas went from the largest to the boldest.

I would like to make a suggestion to the Powers That Be in Greenville. We have a lovely lady who contributed much to the aura of the State of Texas, but who is absolutely unknown in these parts of the state. Actually, she isn’t well-known much of anywhere but she definitely needs to be. She needs to be up there with Dean Hallmark, Monty Stratton, Robert Neyland, Reecy Davis, and others unsung heroes of Hunt County.

The lady, Gladys Yoakum Wright, was a native of Greenville born here in 1891. After her father died when she was quite young, her mother married Charles H. Yoakum, a member of the Texas legislature and outstanding attorney who later became general counsel for the Frisco Railroad.

Gladys grew up in Greenville. She wasn’t much of a musician but was a very good poet. And she dearly loved Texas. You may have heard her famous work. The first few lines are:

“Texas, Our Texas. All hail the mighty State!

Texas, Our Texas! so wonderful so great!

Boldest and grandest, withstanding ev’ry test

O Empire wide and glorious, you stand supremely blest.

God bless you, Texas!

And keep you brave and strong,

That you may grow in power and worth

Through-out the ages long.”

Very dignified, as was most poetry in the late Victorian Age. However, it’s not sung to the tune of a railroad work song. You know the one they sing at UT.

After she married Mr. Wright (who remains anonymous with no known first name or initials), the couple moved to Fort Worth. In 1923 Governor Pat Neff thought the State of Texas needed a state song. After all there was a state tree, a state bird, and our beautiful state flower. He issued a challenge to the citizens of Texas and offered $1,000 in donated prize money to the winner.

A total of 286 songs were submitted. Friends of Mrs. Wright suggested she and William J. Marsh join forces in the competition. Marsh was a trained musician and professor of organ at TCU. They put Mrs. Wright’s poem to Mr. Marsh’s equally dignified music.

It took two days for Governor Neff to select the official song for the State of Texas. Five days before his term ended, Governor Neff announced the choice, Texas, Our Texas. But, you know how the Texas Legislature operates. It would be March 11, 1930 before Gladys Yoakum Wright and William J. Marsh would learn their song and Pat Neff’s choice was the new State Song of Texas. I hope they received the prize money.

Here’s a link to hear “Texas Our Texas” provided by the Texas Chamber of Commerce. Ironically, they only list William J. Marsh as the song’s author.

Today we proudly sing Texas, Our Texas. Or at least we should. And why not spread the good word about Gladys Yoakum Wright, Greenville’s darling poet?